For this week’s Sunday Visit interview series, we are delighted to feature Madeleine MacGillivray, a lifelong climate justice advocate, science communicator, and sustainability expert. From founding her first climate project at the age of nine to serving as the Climate Communications and Policy Coordinator at Seeding Sovereignty, Madeleine has dedicated her life to addressing the urgent intersections of plastics, climate, and environmental justice. With an MSc in Sustainability Management from Columbia University and extensive experience in microplastics research and advocacy, she brings a unique blend of scientific expertise and grassroots activism. Join us as we explore her inspiring journey, her fight for systemic change, and her vision for a more sustainable future.

Could you explain the concept of the “pipeline to plastic” and its implications for climate change?

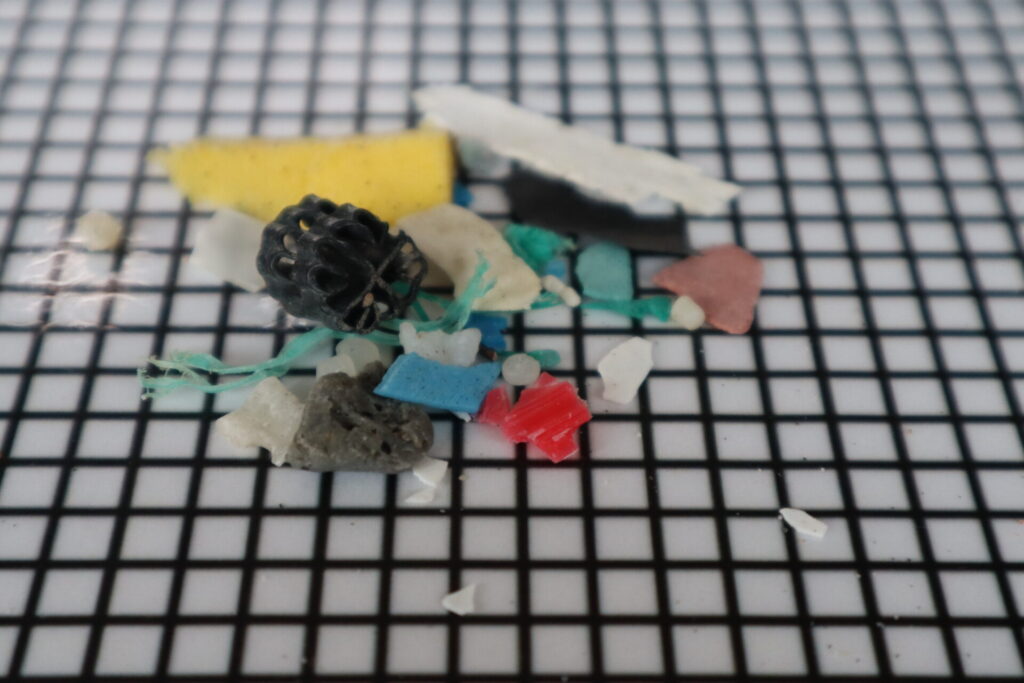

‘Pipeline to plastic’ highlights the connection of the pipelines that transport extracted oil and gas from the depths of the Earth across land and water, destroying ecosystems and communities, only for those oil and gas products to be refined into plastics that are produced at ever increasing volumes and poison, our land and bodies further as micro and macroplastics. This is why plastic is a climate issue— not only does it take from The Earth and produce greenhouse gases, but it also poisons us and our environment in the form of plastics that are affecting earth’s systems and our communities.

You’ve mentioned that the majority of microplastics are fibers. How does this fact influence your approach to tackling plastic pollution, especially in relation to the fashion and textile industries? As a natural dyeing company this is something we really take to heart.

Yes, absolutely this is a critical conversation: over 1/3 of micro plastics in the oceans are actually microfibers from clothing and textiles. And I want to make a very important distinction: when I say microfibers, I’m not just talking about synthetic fibers that are produced from oil and gas and spun into fibers that get woven into a fabric. I’m also talking about plastic products that go into dyeing and treating fibers. This is why natural dyeing processes and processes that produce clothing without extracting and using oil and gas are absolutely critical in the shift towards climate justice.

You’ve been involved in climate activism since a young age. How has your perspective on environmental advocacy evolved since your early experiences, such as the Our Children’s Trust lawsuit?

I am so lucky to have been one of five youth plaintiffs in a landmark lawsuit when I was 15 years old. We sued the EPA for Climate in action and that case started the now decade plus of youth climate lawsuits having participated in such a powerful moment at an early age showed me how thin the barrier to confronting government head on actually is. Folks need to know that you are elected officials, your representatives, are not somewhere off in the distance and inaccessible to you. You can go to them today demanding what you need to demand and realize that they actually work for us and we have the power to vote them out if they don’t. Do not wait for somebody else to do something that you wish would happen. You have to be the person to do it.

That’s so inspiring! In your work, you often emphasize the importance of storytelling and community building. How do you use these approaches to communicate complex scientific information to your public? One of my favorite questions you ask people is WHAT IS YOUR SUPERPOWER? Can you tell us yours and why that question is so integral to the work you do?

Storytelling is so needed right now. Climate has a huge branding and storytelling problem, I say this all the time. We need to share more real and beautiful, raw stories that bring us closer to each other. I love communicating information on plastics and science in a way that might land for people. That bridges the silo between the Ivory Tower and information that is often gate kept from the rest of us. Speaking to this, I think that is definitely one of my superpowers. We all have our own very unique superpowers that come from what we’ve experienced in our lives, the things that light us up and make us feel alive, and the issues that we really care about. Acting from our superpowers is what brings us the most joy and will sustain us in this lifelong pursuit for justice. This is not the work of the next five or 10 years. It is the work of lifetimes.

What are some of the most pressing policy changes you believe are necessary to address climate pollution effectively? Can you tell us about the new project you are working on?

The thing is, there are some really important federal policies that need fighting for like carbon tax extended producer, responsibility, and making polluters pay for their destruction. But one thing that I really need to highlight for people is that the most effective policies happen at the super local level. And there are so many Climate justice bills that your legislators are proposing that really need your help in order to pass, but they’re sitting there because nobody knows about them. I’m really excited about a project that we’re working on it. Seating sovereignty is called the Climate policy action portal. I developed it to tackle this problem of in accessibility When it comes to every day folks becoming advocates for really important climate policies.

How do you see the relationship between microplastics pollution and environmental justice issues, particularly for indigenous communities?

Seeding Sovereignty was founded at Standing Rock, in direct response to the fight against the destructive Dakota access pipeline that would run through indigenous lands and poison water. Indigenous folks have been on the front lines of the most extractive and exploitative colonial fights for hundreds of years, and continue to bear the brunt of environmental destruction on their health at all stages of extraction. We are working on a project that would build solidarity with folks on reservations and other black and brown communities across the country that would empower people living with low waist infrastructure and next to industry with the tools to test their drinking water for micro plastics and be able to own their own stories to bolster our collective fight for environmental justice.

You’ve described yourself as an “empathist.” How does this perspective influence your approach to environmental advocacy and science communication?

Empathy as a way of being in all infinite moments of life is in my view how we become free. I am you and vice versa, and what I mean by “empathist” is one who embodies empathy as a verb in the everyday. Without a serious spiritual revolution, comprising millions of individuals to look more deeply within ourselves, the world that we know can exist won’t. For those of us who lead with empathy, we must — and this is usually not in our nature — do it loudly.

Looking ahead, what do you see as the most promising solutions or areas of research in combating microplastics pollution?

Well, we cannot recycle our way out of the plastic’s problem. We must scale back and fight for a post growth society. And there are so many solutions that must happen at the same exact time in concert with each other. I emphasize that the micro plastics issue is not a micro issue. It is connected to fossil fuel extraction to the clothes that we wear to The politicians that we elect start really really small by figuring out the spaces that you exist inside of on a daily basis and where plastic show up in ways that is super unnecessary and how you can advocate for that to change like right now.

On a larger scale, we absolutely need to be pushing for legislation that makes large producers pay for their pollution and destruction, and for our governments to fund more in-depth research on the human harms of micro plastics in our bodies.

Loved this interview and thank you Madeleine