Natalie Stopka’s work lives at the confluence of artistry, ecology, and inquiry. A bookmaker and pigment artist attuned to the language of materials, she explores the cycles of growth, decay, and transformation through color coaxed from the natural world. Her studio practice feels like collaboration rather than control—an ongoing conversation between plant, hand, and time. In this week’s Sunday Visit, Natalie opens the doors to that world, where books are bound with patience, pigments ripen through experiment, and the intimacy of observation becomes a creative act in itself.

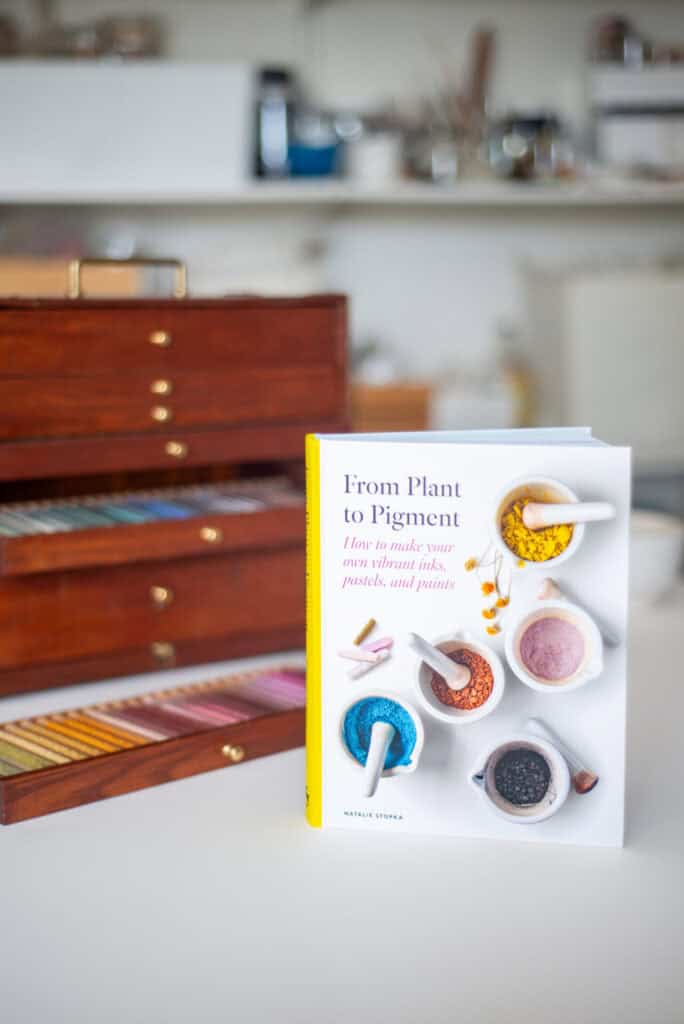

Her new book, From Plant to Pigment, grew from years of teaching and field research, answering the call of a community eager to revive a nearly forgotten craft. Once eclipsed by synthetic dyes, botanical pigment-making is finding new relevance in today’s studios, and Natalie has created a resource that bridges historical practice with accessible experimentation. The book invites readers to rediscover awe in the ingenuity of our artisan ancestors while demystifying the chemistry of color—transforming what might seem like alchemy into a joyful, grounded craft rooted in respect for plants, place, and process.

What inspired the creation of “From Plant to Pigment,” and what do you hope readers will carry with them after diving into your studio practice with botanicals?

I was persuaded to write From Plant to Pigment by the enthusiasm of the artists, craftspeople, and creatives showing up to natural dyeing and pigment workshops with a host of questions and a dearth of good resources for answering them. The craft of botanical pigments fell out of fashion 150 years ago with the advent of the Synthetic Revolution, but folks are reconnecting to the heritage of handmade & local color today. It was clear that a contemporary guidebook would be a great studio resource.

I hope that readers will discover a spark of awe for the beauty of plants, and respect for the ingenuity of our artisan forbears whose pigments inspired the recipes in the book. On a practical level, I hope readers gain insight into the chemical underpinnings of dyes, mordants, and pigments, such that they can have fun with pigment-making rather than feel intimidated by it.

What first sparked your interest in natural plant color, and how did that curiosity evolve into a full-fledged artistic exploration?

The seed was planted in my childhood, dyeing hanks of yarn with onion skins from our garden; my mother is a textile designer and gardener. After attending art school I studied bookbinding, and became tired of the staid palette of available materials. I recall a eureka moment of realization that books used to be made entirely from natural, laboriously processed materials: thread, paper, glue, leather, fabric, dye, pigment, ink, gilding…. And that such materials were more eloquent, specific, and true than synthetic counterparts. My exploration started with naturally dyed paper, thread and book cloth, and expanded to lake pigments when I traced the history of marbling back to pre-synthetics. I discovered that marblers used many different shades of lake pigments, and knew I wanted to crack the code and make my own.

How has your process changed from when you first began extracting color from plants to now, in your bookmaking and art practice?

As in any new undertaking, I started natural dyeing with a lot of enthusiasm and the kitchen sink (literally and figuratively). I was thrilled with any color outcome! The more practiced I became, the better I understood why our best practices exist. These govern fiber handling, plant selection, and mordant ratios, and are verified by generations of artisans’ observational proto-chemistry. Just as with cooking in the kitchen, these best practices become instinctive over time, and are the bedrock supporting our creative filigrees.

Today, I nurture both a research practice and a creative practice. The former is a fairly rigorous experimentalism: I summon hypotheses, devise experiments, take notes, and make comparisons to a control group. This research supports both my teaching and my creativity, giving me insights into why our ingredients behave the way they do, and how we can express ourselves through them.

What role does embracing the unexpected or mistakes play in your creative process, and are there any memorable “wrong turns” that shaped your path?

I absolutely believe in following the lead of materials, helping them to express themselves in unforeseen ways. One autumn night, I left a tray of paper I was dyeing outside to steep. In the morning I discovered it had been frosted, and ice crystals left the delicate imprint of their texture on the paper. This surprise begot a series of diptychs titled Riming.

How does your relationship with place—the soil, water, and local ecology—inform the way you select and use materials?

The key word in your question is relationship. Part of my studio practice is stewarding my own relationship to place, which is a constantly, quietly growing awareness of the natural world. I’m always learning more about botany, soil, plant identification, watershed, elements, and ecology. I guess I’m trying to become suggestible; open to the materials proffered by place.

A few years ago, I learned that historical green and yellow pigments were made from buckthorn. This shrub is a designated invasive species where I live. I tramped up and down hiking trails, circled the edges of fields and parks, looking for buckthorn. I finally found it, and now that I’ve befriended this overabundant species, I can spot it from 50 yards! And I can responsibly forage its berries, transmuting a vilified weed into beautiful pigments. Instead of purchasing exotic dyestuffs, I can better tell the story of my local ecosystem utilizing foraged plants, including the most multitudinous ones.

Are there artists, writers, or scientists who have influenced your philosophy of color and making?

The Art and Science of Natural Dyeing (Boutrup/Ellis) is a must-have for explaining why the best practices of natural dyeing work. It explains in digestible terms the chemistry underpinning our craft. Phillip Ball’s Bright Earth looks at how the technologies of color production have shaped art history. It is so exciting to see new books on natural and historical art materials coming out from Heidi Gustafson, Caroline Ross, Julie Beeler, Lucy Mayes, and others! In the bigger picture, I enjoy reading Tim Ingold and Pamela H. Smith exploring how artisans engage with materiality and create knowledge.

Could you share a glimpse into your typical studio day when developing new botanical pigments—what’s on your worktable, and how do you begin?

For me, working with natural materials is an ongoing conversation in which I gradually draw them out, suss out their propensities, and overhear inklings of their potentiality. I start by asking a question: What can you do? I then devise an experiment whereby the materials can answer. Because natural dyes are incredibly reactive and expressive, color variations are produced by changing growing conditions, harvesting time, mineral and pH modification, extraction time, temperature, and method…these are some of the variables I am tugging at.

I usually receive hints from other artisans current and historical. I love reading historical dye manuals and books of secrets, so I always have a stack of reference books on my desk and a tab open to the Internet Archive or Library of Congress. I keep a spreadsheet updated with data on all the experiments I’m working through. Lake pigments take a few days, so I often have 3-6 going at once…and a slop sink full of dishes to keep up with the pace of pigment-making!

What is your approach to cultivating, foraging, or sourcing dye plants, and do you have any favorite seasonal ingredients?

My ideal is to follow the thread of abundance: those plants I can bountifully grow in my garden conditions, those that proffer themselves for foraging, and the overabundant species whose omnipresence hampers biodiversity. I love growing weld and indigo, and have a big pot of madder that’s 2 years old. Goldenrod, buckthorn berries, and flag iris root are favorites for foraging. I try to keep stocking the studio larder throughout the year – not only with plant material during the growing season, but seeds and galls in the autumn, and wood ashes and charcoal in the winter.

How do you balance concerns about lightfastness and permanence with the beauty of fleeting colors?

In practical terms, I choose the right pigment for the right application and degree of light exposure. In conceptual terms, what is ephemeral is precious. Working with natural colors requires artists to be awake to the aliveness and dynamism of nature – to be present at the moment to harvest indigo or gather oak galls. We implicitly ask our viewers to do the same: be present to receive fleeting beauty and appreciate the changingness of all things.

In “From Plant to Pigment,” what recipes or techniques are you most excited for readers to experiment with?

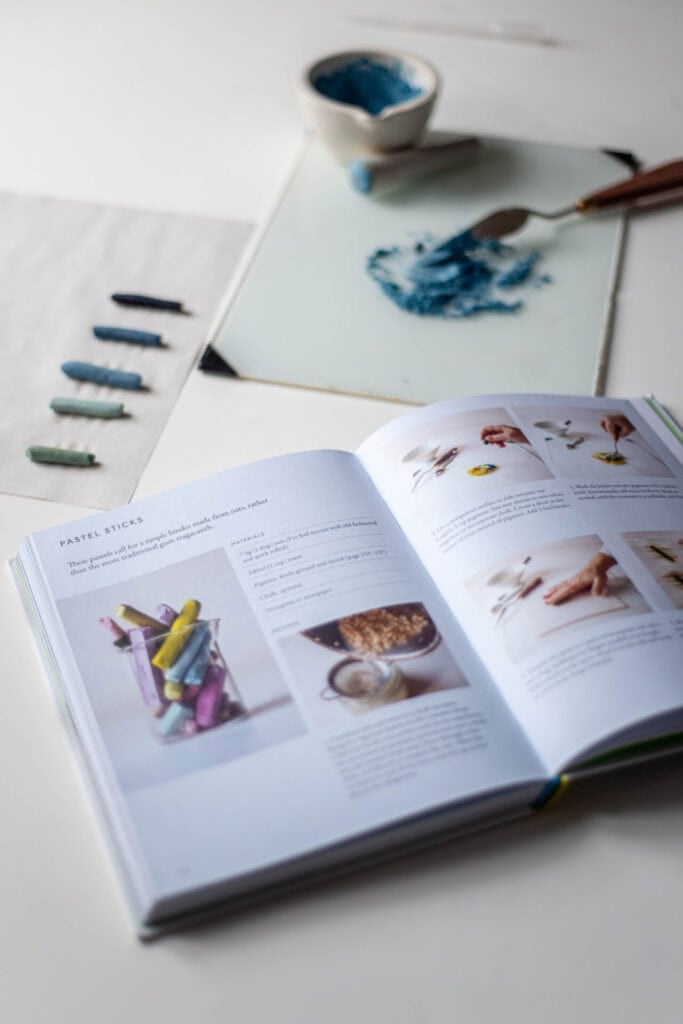

I am excited for pigment-makers to create really vibrant, rich colors by controlling the ratio between dyestuff and alum! Not pale pink, RED. These colors low on the value spectrum are so versatile in the palette. The Dyestuff Ratios Chart (p. 70) will be a boon to making them.

I’m also keen for both pigment-makers and dyers to expand into extraction methods beyond the usual hot water extraction. It’s tried and true, but other methods can stretch our color yield and influence its hue. To that end, I’ve included instructions for Ice Maceration, Tincture, Alkaline Extraction, and Fermentation. Let’s all start fermenting stuff!

As an educator, how do you encourage students (and readers) to embrace hands-on, experimental approaches with natural color?

A little light chemistry brings control, and history provides context to color-making. I love sharing the backstories of pigments and plants because each color is connected to cultural heritage, plant stewardship, local ecology, and artistic expression. There’s something for everyone to get excited about.

I’ll be sharing these stories and supporting hands-on learning in a new series called Cook the Book! Starting in February, this eight-part online series will progress through the recipes of From Plant to Pigment, allowing participants to quickly learn the operative chemistry of botanical pigments and stock their studios with colors ready to create art.

If you could suggest one entry-level project for someone new to botanical pigments, what would it be?

I’d suggest following the Master Lake Pigment Recipe (p. 63), using one of the plants listed in the Dyestuff Ratios Chart. Then, turn that pigment paste into a Speedy Paint (p. 150) for the gratification of a richly-pigmented paint without special equipment or extra drying time. Very approachable and colorful.

Looking back, what surprises you most about your artistic journey or the evolution of your relationship with color?

I am so surprised and delighted to find a supportive community of fellow artisans likewise questing for handmade, homegrown, regenerative art materials. There are a lot of us nerds re-forging connections to the heritage of natural color, and ushering it into the future. It’s an honor to be in the club.

Where do you see your work — and the field of handmade pigments — heading next?

I sense that artists and dyers are becoming increasingly hyper-local in their plant sourcing. Growing and seed-saving the ecotypes best suited to our particular conditions, practicing water-wise growing and dyeing, foraging the species that are most abundant, and branching out to explore plants that aren’t necessarily documented in dye manuals. I see this bringing a real specificity to our palettes, reflecting the ecology, terroir, and our own commitment to engage meaningfully with plant color.