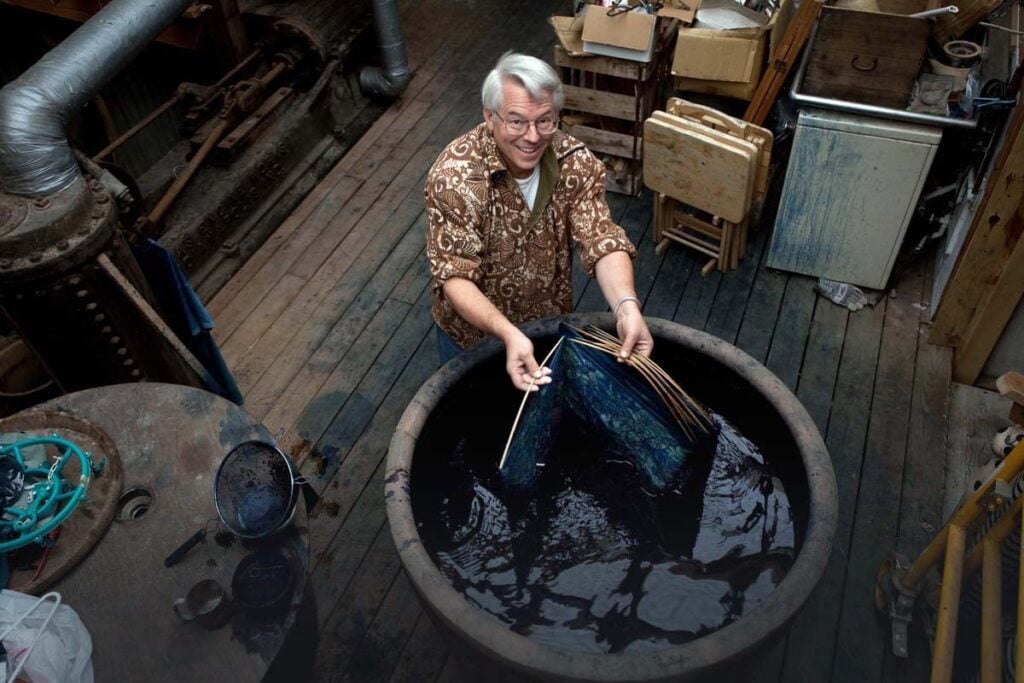

For Sunday Visit, Botanical Colors sits down for an interview with a luminary in the natural dye, textile and art world. This week we visit with none other than internationally known and revered textile artist John Marshall, an expert in Japanese textile techniques and all around funny guy. Grab a cup of tea and settle in to learn about someone you never knew! Catch up on all our Sunday Visits here.

Cara: I had a really fun time visiting your website and learning a little bit about your history, You have had an amazing practice and career. Can you tell us about your origin story? I read that you grew up in a Japanese American community in a town close to Sacramento. Tell us about how that started your path into natural dyes and how you got to where you are today?

John Marshall: I grew up in the tiny town called Florin, and the population was largely Japanese American, although it was a mix of a broad range of people. You know, that’s one of the strengths I think of the United States is that we have such a diverse range of influences. It gives us a lot more to pull from: sort of like genetic diversity always gives you strength. So growing up in that community, I was exposed to all sorts of Japanese things like Japanese textiles, Japanese dolls and culture that was just part of everyday life.

Among the people in the community were my godparents Al and Mary Tsukamoto, Mrs.Tsukamoto in particular was instrumental in my interest. She was also my fifth grade elementary school teacher. And being a tiny town that Florin was at the time meant that everybody knows everybody. And so she was my godmother on the outside, but my school teacher on the inside, and she brought Japanese things to class.

Now, you have to remember this was the early fifties. It wasn’t long after World War II. After Pearl Harbor was bombed, both of my godparents and everybody else in town was sent to the concentration camps. So imagine then only a few years later she wanted to start teaching us Japanese language and culture in the classroom, but she was afraid that might cause problems. And so she went to the principal and the principal said, just don’t tell me about it, do it. And, as it happened, we had kids come from Japan that year, like exchange students. My godmother’s Japanese was very Americanized, but she at least could speak to them. She was the teacher that could help them. So while she taught them English, she taught us Japanese language and culture, and I grew to love the dolls that she collected and shared with us. So later then when I was 17, having graduated high school a year earlier, I went to Japan to study. That’s where the formal training began. I was apprenticed in doll making. In doll making, we had to learn how to blow the glass for the eyes. We had to learn how to choose the branch to carve, to cut from the tree, to cure it. to carve it, to weave the silk for the textiles, to do the dye work for the textiles. None of it was a really deep knowledge and there’s a Japanese expression, asabiroi, which means shallow but broad.

I don’t need to know how to do exquisite opulent weaves. I need to know how to do enough for the doll. If I’m doing wood carving, I don’t need to know how to carve a masterpiece. I need to know how to carve a face. Okay, so in that context, I was trained in a very broad range of things on a shallow level, but that gives an appreciation and an understanding of what goes into them. And that’s what I work to communicate to people, not only through textiles, but other elements, like dolls and and other facets of Japanese society.

C: Wow, thank you so much for sharing all that. I feel like like the doll making itself is kind of this wonderful analogy for life, it still feels like there’s so much dedication and care, even though it feels shallow and broad, you know, in today’s society. What a special gift to receive. That kind of an education where you holistically are working on the carving, the plant that you have to choose, the making of the textile, making the glass. You get a complete education in making just one object.

Cara: Can you tell us a little bit about that and like your joy of creating books as well and sharing your knowledge that way?

John Marshall: The next book coming out is called Salvation through Soy. People have asked me how I came up with the title. Well, soy milk is an integral part of Japanese dyeing and diet. I found an online reference about this minister who claimed that soybeans are the food of the devil and he has proof. His proof is that Asians eat them. Okay. I thought, Hmm, well, can’t let that go. So the entire book is Salvation Through Soy. I kind of do that a little bit – tongue in cheek – through the whole book in terms of how soybeans benefit us and bless our lives. It’s done partly as a joke, but unfortunately, so much of our information available in the States – manuals and things – seem to have no joy, seem to have no humor in them. And they still communicate the information, but not something you always want to go back to. So in my publications, I try to introduce a little bit of humor. It’s my quirky humor. So it might not agree with you, but that’s the basis of the book. It covers all of the different ways of using soy milk. There are lots of projects and so forth. Botanical Colors will be carrying it. I hope people will benefit from the knowledge that I share.

This was so interesting. My baby sister would have died without soy milk. When she was born, she had an awful allergic reaction to milk and all she could tolerate was soy milk. It smelled yucky.

Also, my uncle was stationed in occupied Japan following WWII. My aunt sent me a beautiful Japanese doll which I cherished forever and passed on to my granddaughter. Thank you. Susan Terrill